“I can only say one simple dictum,” German filmmaker Werner Herzog expressed in an interview with VICE magazine, “[that] the world reveals itself to those who travel on foot.” The aphorism’s sentiment is shared by Herzog’s contemporary, and fellow Teutonic director, Wim Wenders in his film Paris, Texas. Released in 1984 and premiering at the Cannes Film Festival, it quickly garnered critical acclaim, winning all top three awards—a triple crown—and cementing Wenders as an acclaimed auteur of the New German Cinema movement.

But what most captivates me is the film’s interaction of actor and setting, which provides a clear glimpse of a moment in time when American and European attitudes toward urban and provincial travel were shifting. It’s hard not to conjure mental images of a cars, but Herzog and Wenders advocate walking as a more conducive and conscientious means of self-actualizing than driving could ever accomplish.

Paris, Texas introduces us to Travis, played by the everlastingly languid but always exceptional Harry Dean Stanton, a speechless and catatonic soul walking aimlessly in the Texan desert while wearing a tattered chalk-strip charcoal suit. When Travis stumbles into a desolate gas station, he collapses from heat exhaustion. Once a doctor revives him, Travis’s older brother Walt (played by Dean Stockwell) is informed of his younger brother’s whereabouts. Walt leaves his Los Angeles home to come to the aid of his brother, whom he has not seen in four years. After leaving the clinic, he seeks asylum in the vastness of the southwest, and when the two siblings reunite not too far from the clinic, Walt says, “You look like forty miles of rough road,” remarking on Travis’s lack of sartorial decorum and the restlessness that comes from having been momentarily interrupted from his walking journey.

Throughout the first act, Travis is reluctant to be a passenger in Walt’s rented sedan, as Travis is accustomed to walking as a means of disassociating from all his emotional trauma—the failed marriage, the escalating drinking, the absentee father that he is. However, Walt is a therapeutic figure, gently coaxing Travis into speaking again and regaining some emotional footing. Despite several early failed attempts to flee the motel the siblings are staying at, Walt’s investment in Travis makes him feel more comfortable about car traveling.

The middle act moves the narrative to Los Angeles, as Walt reintroduces Travis to his biological son, Hunter. Hunter is now six and has been living with his Uncle Walt and Aunt Anne for the last four years, but Hunter is more skeptical than upset at Travis.

What unfolds narratively thereafter is a series of small cinematic gestures wherein Hunter and Travis attempt to bond in a suburb of Los Angeles. “Nobody walks, everybody drives,” Hunter says, yet despite his early reservations, Hunter later relishes the opportunity to walk with Travis from school. “Who is that guy? You know him?” Hunter’s friend asks while staring at Travis standing patiently at the corner. “Yeah, he's my father's brother. No, they're both brothers. No, they're both…they are both fathers. No, forget it. Both whose fathers? My fathers. H-how how can you have two fathers? Just lucky I guess.” Travis and Hunter never convene onto the same sidewalk. Rather, they pantomime each other’s behaviors while simultaneously walking. Walking and engaging Hunter on his level of humor enables Travis to no longer self-medicate through the aforementioned dissociation of his emotions. Instead, Travis has begun to cognitively heal and actively gain awareness and the emotional faculties necessary to move on. Walking has become a tool to engage in this awareness, repurposed and refurnished from his previously counterproductive practice.

But beyond Travis’s growth as a character lies what is perhaps the real star of Paris, Texas, a polarizing figure. That figure is the iconic American urban highway. To my marvel, it took a Germanic director to film and take a sociological lens to the zeitgeist of 1980’s American travel, specifically the highway, with its overbearing overpasses, mixing bowls, and multiple lanes. The modern highway suffocates Mother Nature, and when we follow our natural inclination to walk on foot and acquaint ourselves with our surroundings, the highway violently disrupts our serenity. In Paris, Texas, we witness the historical significance of freeways decimating the southern California valleys, yet Travis, with a set of binoculars, is constantly observing these monolithic infrastructures from the hilltop view of Walt’s home. In the highway, he sees the opportunity to find his estranged wife and have the nuclear family he so desperately craves.

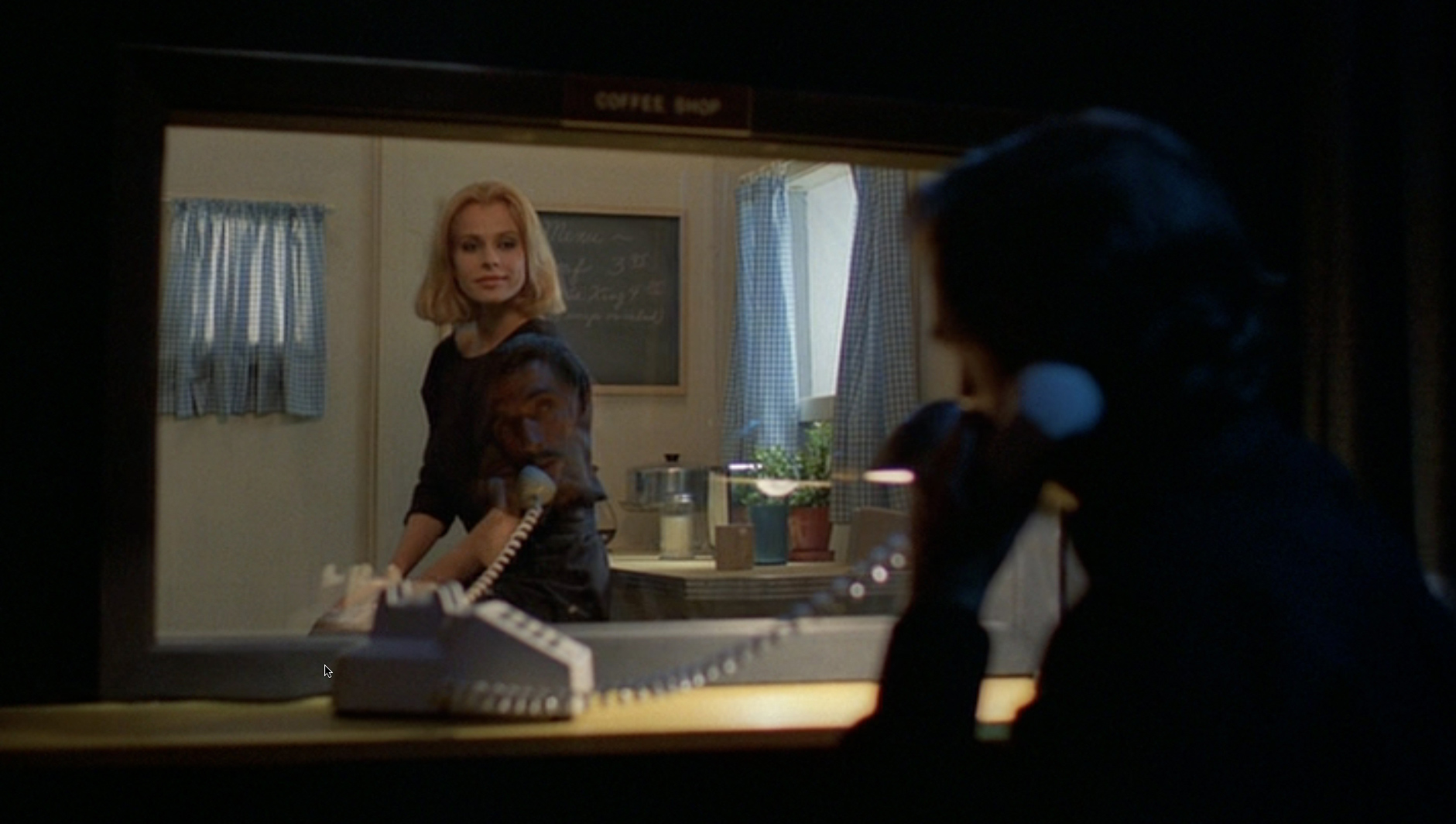

The most jarring scene visually occurs when Travis hears news that his estranged wife, Jane, is currently residing somewhere in the sprawl of Houston. The act of reunifying could force Travis to confront his past and potentially undo all the progress to his fragile psyche. This notion weighs heavily, and Travis embarks on another aimless, yet local and shortened, walk. Whether he is disassociating as previously, or cognitively processing and actively prepping his psyche, the film does not reveal. At last we come to the point where Travis walks across an overpass that is stationed above a ginormous, double-digit lane highway. Wim Wenders skillfully adds a layer of Euro cinematic panache to Paris, Texas by purposely foregrounding the background. The highway becomes a visual cue to the character’s psyche—overwhelming, fatiguing—but the highway also provides salvation. A salvation of a reunited and repaired three-person family unit.